Companies with a negative enterprise value are elusive beasts, highly sought after by deep value investors, but little understood outside that world.

Value investing is about finding and buying a bargain, a dollar selling for 70 cents or less. One of the most tantalizing apparent bargains offered by the stock market is the negative enterprise value (EV) stock: a stock that is trading for less than the net cash on the company’s balance sheet.1 Buying a negative EV stock seems like a no-lose proposition: Imagine a house selling for $1 million with a safe in the basement that contains $1.2 million in cash. Why would anyone offer up such a deal? If you find one, should you take it, or write it off as too good to be true?

To answer this question, I investigated the performance of all negative EV stocks trading in the United States between 30 March 1972 and 28 September 2012. I started with balance sheet data from Standard & Poor’s Compustat database and merged these data with price data from the database maintained by the Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP). I then calculated historical enterprise values for every company every month, as well as matching forward 12-month returns. For example, Microsoft’s enterprise value on 31 August 2011 was $182 billion, and MSFT’s 12-month forward return from 31 August 2011 to 31 August 2012 was 19%. This is a total time-weighted return, including dividends and price appreciation. The enterprise value is based on Microsoft’s 2011 Q4 report, which was released on 21 July 2011, making it 41 days old on 31 August 2011. The merging process ensures that all fundamental data have been published to the market at least five days before they are used in EV calculations so as to minimize look-ahead bias. After this math was done, I filtered the dataset to include only negative EV stocks.

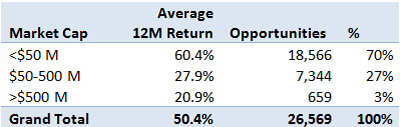

I found 2,613 stocks that at one point or another traded at a negative enterprise value between 1972 and 2012 (Microsoft, unfortunately, was not among them). The list has one entry per stock-month. That is, a stock that has traded at a negative enterprise value three months in a row will appear on the list three times. Each time is a different investment opportunity with its own forward 12-month return. The average stock spent 10.17 months (not necessarily consecutive) in negative EV territory. Thus, the list shows a total of 26,569 opportunities to invest in negative EV stocks.

The average return across all 26,569 opportunities was 50.4%. That is, if you had diligently watched the market over the last 40 years and invested $1,000 into each negative EV stock each month, your average investment would be worth $1,504 after holding that investment for one year, not including trading costs, taxes, and so on. Not bad!

As it turns out, this strategy works much better for individual than larger institutional investors because most of the investment opportunities are in micro-cap stocks with limited liquidity:

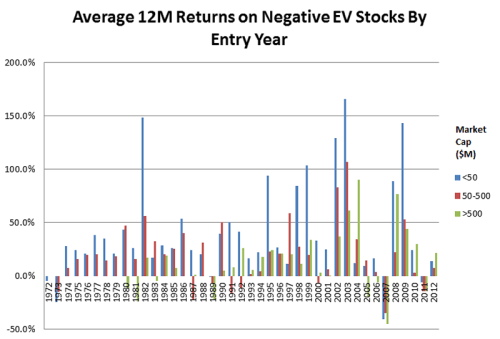

Only about 3% of the investment opportunities are in stocks with a market capitalization of half a billion dollars or more. These opportunities have come up with some regularity and have usually provided attractive returns but have on occasion lost a great deal as well:

In summary, negative EV stocks have offered attractive returns over the past 40 years and may be well worth a look, provided you can stand the volatility.

Alon defines enterprise value is defined (EV) as follows:

- EV =

Common equity at market value (this line item is also known as “market cap”)

+ Preferred equity at market value

+ Minority interest at market value, if any

+ Debt at market value

+ Unfunded pension liabilities and other debt-deemed provisions

– Associate company at market value, if any

– Cash and cash-equivalents.A negative EV stock is one where the cash exceeds all other factors in the equation. In practice, “cash” may be defined to include marketable securities. In that case, the marketable securities themselves may be over- or undervalued.

Read more: Returns On Negative Enterprise Value Stocks: Money For Nothing?

There are several negative enterprise value stocks in the All Investable and Small and Micro Cap Screeners. Check them out.

For all the latest news and podcasts, join our free newsletter here.

Don’t forget to check out our FREE Large Cap 1000 – Stock Screener, here at The Acquirer’s Multiple:

12 Comments on “Negative Enterprise Value: A Primer”

Pingback: G Willi-Food International Ltd trading at a discount to its NCAV $WILC | Stock Screener - The Acquirer's Multiple®

Hey man!

What about negative Acquirer’s multiple? Is it something to avoid or is it a good thing that it’s negative?

Yep. Negative EV is good: https://acquirersmultiple.com/2015/10/negative-enterprise-value-a-primer/

With such incredible returns, why is there so little research on negative enterprise value stocks. It seems that they act much like net-nets (possibly better) and yet there is significantly more research on net-nets.

The stocks look like trash. Hard to persuade someone it’s a good idea, even if the balance sheet is pristine, when the business is ugly.

I get that a negative EV is good, but what about a negative acquirer’s multiple? What if the EBITDA is negative?

Does one then just ignore the minus symbol in front of the result?

Negative EBITDA is bad. Negative acquirer’s multiple with negative operating income is bad.

Negative EV is good. Negative acquirer’s multiple with negative EV is good.

Short and to the point! Thank you!

Sir Tobias Carlisle

In a case where positive EV and negative Operating Earnings..

Is it worthy stock

In second case both EV and operating earnings are negative and resulting Acquires Multiple positive

In such cases what should an investor do?

Regards

A negative enterprise value is good. A negative acquirer’s multiple caused by a negative ev is good. A negative acquirer’s multiple caused by negative op. inc. is bad. More here: https://acquirersmultiple.com/2015/10/negative-enterprise-value-a-primer/

Is Negative EV a better strategy than NCAV in terms of CAGR?

Hi Tobias,

In your book Acquirers Multiple you applied 5x to 6x multiple to get the EV value for See’s between 40 to 50m. I was wondering how would different levels of debt impact this final value of the business. Would you deduct the debt from the 40 to 50m value? And the remaining then counts as the business value? And, what if debt was let’s say 80m. Would that mean the business value is – 30 to – 40m?

Best regards