In Michael Mauboussin’s book – More Than You Know – he shares a great story about Paul DePodesta and Michael Lewis at a Vegas casino and the lessons investors can learn about getting positive expected value on your side. Here’s an excerpt from the book:

Hit Me

Paul DePodesta, a former baseball executive and one of the protagonists in Michael Lewis’s Moneyball, tells about playing blackjack in Las Vegas when a guy to his right, sitting on a seventeen, asks for a hit. Everyone at the table stops, and even the dealer asks if he is sure. The player nods yes, and the dealer, of course, produces a four. What did the dealer say? “Nice hit.” Yeah, great hit. That’s just the way you want people to bet—if you work for a casino.

This anecdote draws attention to one of the most fundamental concepts in investing: process versus outcome. In too many cases, investors dwell solely on outcomes without appropriate consideration of process. The focus on results is to some degree understandable. Results—the bottom line—are what ultimately matter. And results are typically easier to assess and more objective than evaluating processes.

But investors often make the critical mistake of assuming that good outcomes are the result of a good process and that bad outcomes imply a bad process. In contrast, the best long-term performers in any probabilistic field—such as investing, sports-team management, and pari-mutuel betting—all emphasize process over outcome.

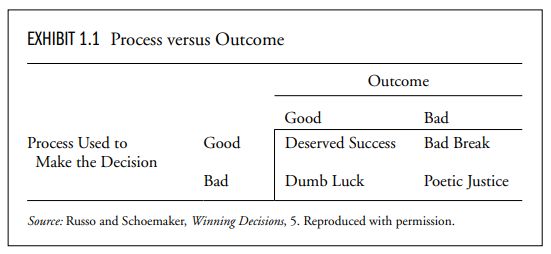

Jay Russo and Paul Schoemaker illustrate the process-versus-outcome message with a simple two-by-two matrix (see exhibit 1.1). Their point is that because of probabilities, good decisions will sometimes lead to bad outcomes, and bad decisions will sometimes lead to good outcomes—as the hit-on-seventeen story illustrates. Over the long haul, however, process dominates outcome. That’s why a casino—“the house”—makes money over time. However, if you’re feeling lucky, you can try your luck online at PG สล็อตเว็บตรง to potentially make some money.

The goal of an investment process is unambiguous: to identify gaps between a company’s stock price and its expected value. Expected value, in turn, is the weighted-average value for a distribution of possible outcomes. You calculate it by multiplying the payoff (i.e., stock price ) for a given outcome by the probability that the outcome materializes.

Perhaps the single greatest error in the investment business is a failure to distinguish between the knowledge of a company’s fundamentals and the expectations implied by the market price. Note the consistency between Michael Steinhardt and Steven Crist, two very successful individuals in two very different fields:

I defined variant perception as holding a well-founded view that was meaningfully different from market consensus. . . . Understanding market expectation was at least as important as, and often different from, the fundamental knowledge.

The issue is not which horse in the race is the most likely winner, but which horse or horses are offering odds that exceed their actual chances of victory. . . . This may sound elementary, and many players may think that they are following this principle, but few actually do. Under this mindset, everything but the odds fades from view. There is no such thing as “liking” a horse to win a race, only an attractive discrepancy between his chances and his price.

A thoughtful investment process contemplates both probability and payoffs and carefully considers where the consensus—as revealed by a price—may be wrong. Even though there are also some important features that make investing different than, say, a casino or the track, the basic idea is the same: you want the positive expected value on your side.

For all the latest news and podcasts, join our free newsletter here.

Don’t forget to check out our FREE Large Cap 1000 – Stock Screener, here at The Acquirer’s Multiple: