Brian Portnoy’s The Geometry of Wealth: How To Shape A Life Of Money And Meaning is a strategic, rather than tactical, guide to wealth. It is strategic in the sense that it asks the reader to consider the purpose of wealth–the ability to afford a meaningful life–as opposed to tactical questions about income, budgets, saving and investing.

Wealth is an important part of a good life. But the getting of it is a confusing, emotional subject. And we are behaviorally ill-adapted dealing with such matters.

Portnoy’s thesis is that, at each stage in life, a well-defined purpose allows us to simplify the big money issues. If we understand our purpose, we can prioritize the right things at the right time. And that makes the practical decisions easier.

Broadly, our purpose is a life well-lived. In this way, Portnoy distinguishes getting wealthy from getting rich. Getting rich is about getting more. It assumes, as neoclassical economists do, that we are utility maximizers–we make rational decisions about the highest and best use of our last dollar. Instead, getting wealth is about achieving funded contentment.

Portnoy defines funded contentment as the “ability to underwrite a meaningful life.” It is necessarily an individual consideration. It is striking the right balance between money and happiness, where money “alleviates sadness more than it inspires joy.” More is only a useful consideration to a point, beyond which the marginal dollar earned is less useful than the time lost to earn it. As such, it is a repudiation of the idea that we are utility maximizers, and an acknowledgment that we are imperfect, and idiosyncratic, the foundation of behavioral economics.

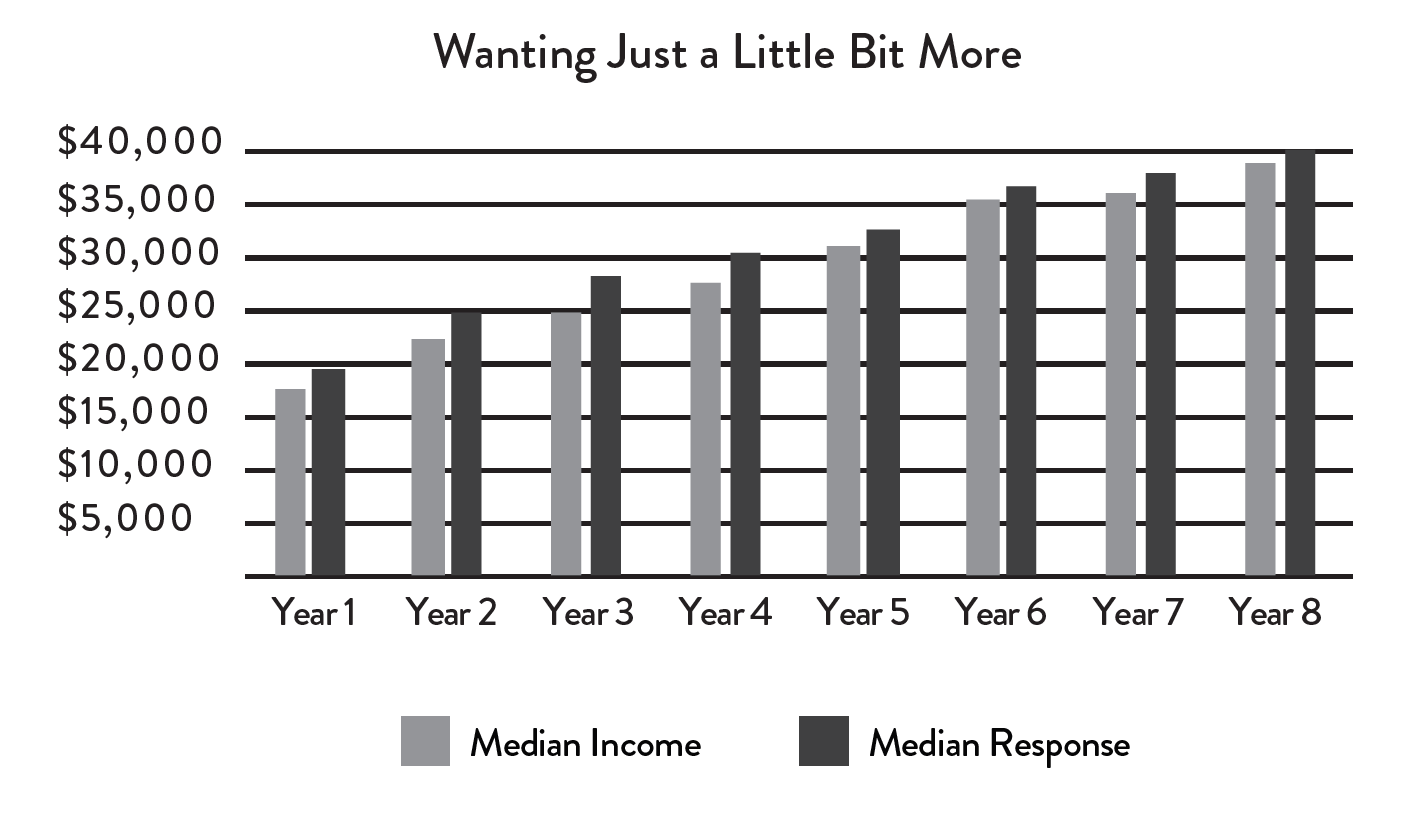

Using the lenses of modern neuroscience and ancient philosophy, Portnoy asks the age-old question, “Does money buy happiness?” This chart contains one of my favorite answers:

Drawn from Juliet Schor’s The Overspent American the chart shows answers to the specific question, “To live in reasonable comfort around here, how much income per year do you think a family of four needs today?” The median answers are set beside the median income of respondents. It shows that from the 1970s to the 1990s, we have consistently believed that we need just a little more to be happy.

To me, the book reads as if it’s aimed at mid-to-late-career, middle-class professionals. Those who have seniority at work, with older kids at home. In other words, those without much time for philosophical questions about the meaning of life. But those who may have reached many of their professional and personal goals, and must now decide whether to “float with the tide, or to swim for a goal,” as Portnoy quotes Hunter S. Thompson. A difficult decision, given the drive to achieve goals is a powerful one, particularly in those who have achieved many goals. Portnoy seeks to guide those folks through a philosophical discussion to the nitty, gritty of the tactics, where the rubber hits the road.

I recommend Portnoy’s Geometry to those who have achieved some success in their professional and personal lives and now ask, “What’s next?” It is a lively consideration of the relationship between money and happiness. Portnoy effectively demonstrates that, for those in the middle-class professional cohort, the quest for more money is an “unsatisfying treadmill.”

Portnoy offers a wonderful conclusion to his book, distilling the book down to a “Tweet,” “Cocktail party” discussion, “Graphic summary,” and individual chapter summaries. The Tweet:

True wealth is funded contentment. Anyone with the right mindset and the right plan can afford a meaningful life.

Disclaimer: I received an ebook of The Geometry of Wealth gratis, and will earn a small affiliate commission from Amazon for any books purchased through the links on this page.